i.

La foto de mi abuela el día de su casamiento

Sé que no lo deseabas

pero lo hiciste.

El buen chico judío asignado

no resultó

tan buen chico.

Pasé tu edad

no me casé con el mío.

Lo deje ir lejos

una noche de luna

en la terraza

tomó mi mano y dijo

no me gustan las chicas

con las uñas pintadas.

Las mías

eran rojas

y dejaban marcas

en las paredes de su intestino.

A veces recuerdo al goy

de la fábrica de máquinas de coser

gritaba tu nombre

en la cueva privada de su boca.

Alegre

soprano de interiores

fósforo

en una caja húmeda

durante un corte de luz

vos empezás a irte

yo recién estoy llegando.

i.

The photo of my grandmother on her wedding day

I know you didn't want to

but you still did.

The assigned good Jewish boy

did not turn out to be

such a good boy.

I am past your age

I didn't marry mine.

I let him get away

a moonlit night

on the terrace

he took my hand and said

I don't like girls

with painted nails.

Mine

were red

and left marks

on the walls of his intestine.

Sometimes I remember the goi*

from the sewing machine factory

he screamed your name

in the private cave of his mouth.

Cheerful

indoor soprano

a match

in a wet match box

when there is a fuse

you begin to depart

I'm just arriving.

* Goi (non Jewish boy)

ii.

Palimpsesto

Me tiré ácido

me raspé la piel

y me escribí encima.

Abajo quedaron huellas

los textos que no llegaron

al canon de mi existencia.

Que vengan los cabalistas

los estudiantes de Talmud

voy a desplegarme sobre la mesa,

una escritura sagrada.

Desnúdenme con cuidado

rastreen los indicios

discutan el estado original

de esta mujer borrada.

ii.

Palimpsest

I threw acid on myself

scraped my skin

and wrote on it.

Traces were left below

the texts that did not make it

to the canon of my existence.

Let the Cabalists come

students of the Talmud

I'm going to spread myself on a table,

a sacred script

Undress me with care

track the signs

discuss the original state

of this erased woman.

iii.

Las copas están hechas para romperse

Lo sé

desde que mi abuela guardaba la vajilla

de su abuela, en un aparador especial

que nunca se abría

por lo delicadas que eran

esas copitas verdes de tallos finos como lirios

capacidad mínima, brillantes.

Nada ameritaba

perturbarlas

de su estado decorativo

los nietos no le habíamos dado

una jupá, un compromiso, un nacimiento.

No le habíamos dado nada.

Pero mi abuela sabía mejor que nadie

que las copas

están hechas

para romperse:

van a quebrarse

mientras lavás los platos

o estallar contra el piso cuando levantás la mesa

un día que estás sobrepasada

o se le van a caer a tu nieta, dentro de veinte años,

cuando se mude sola a su primer departamento.

Van a resistir

como las personas viejas resisten

hasta quebrarse

un día cualquiera de sol.

iii.

GLASSWARE ARE MADE TO BE BROKEN

I know

since my grandmother put away the crockery

of her grandmother, in a special sideboard

she never opened

because of how delicate they were

those little green glasses with thin stems like lilies

bright in miniature capacity

Nothing was worth

disturbing them

from their ornamental state

grandchildren hadn´t give her

a chuppah*, an engagement, a birth.

We hadn't given her anything.

But my grandmother knew better than anyone

that glassware

are made to be broken

they are going to break

while you wash the dishes

or explode on the floor when you ´re clearing the table

stressed out

or your granddaughter will drop them in twenty years´ time

when she moves into her first apartment alone.

They will resist

as old people resist

until breaking

any sunny day.

* chuppah: a Jewish wedding

iv.

Cuando venga el Mesías van a curarse todos los enfermos

pero el tonto va a seguir siendo tonto.

Refrán Idish

Cuando venga el Mesías

y reconstruyan el Tercer Templo

no quiero estar arriba

mirando a los hombres rezar

en círculos que cantan y bailan

mientras mujeres charlan

y chicos gritan.

Cuando venga el Mesías

no quiero estar arriba

con el humo de los sacrificios

abajo los sacerdotes entran

y salen como amantes

pronunciando

el nombre sagrado.

Cuando venga el Mesías

y todos retornemos a la tierra

quiero estar en la tierra de este mundo.

iv.

When the Messiah comes, all the sick will be cured.

but the fool will remain a fool.

Yiddish saying

When the Messiah comes

and they rebuild the Third Temple

I don't want to be above

watching men pray

in circles singing and dancing

while women chat

and children shout

When the Messiah comes

I don't want to be above

with the smoke of sacrifices

the priests entering below

and exiting like lovers

pronouncing

the sacred name.

When the Messiah comes

and we all return to earth

I want to be on the earth of this world.

v.

Teléfono fijo

Mis papás me dieron un teléfono fijo

la línea está incluída dijeron

tenelo por las dudas

y quedó en el piso

cuando suena, rara vez

sé que son ellos

(nadie más tiene el número)

me siento en el sillón

espero tres tonos y atiendo

a veces una noticia terrible otras

una invitación para almorzar

lo único fijo este teléfono.

v.

Landline

My parents gave me a landline

the line is paid for they said

keep it just in case

and it stayed on the floor

when it rings, rarely

I know it's them

(no one else has its number)

I sit on the couch

I wait three rings and answer

sometimes terrible news other times

an invitation for lunch

The only fixed thing this phone.

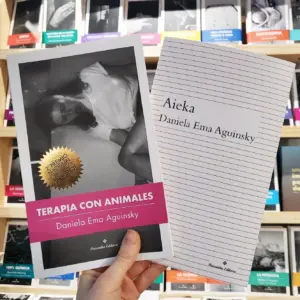

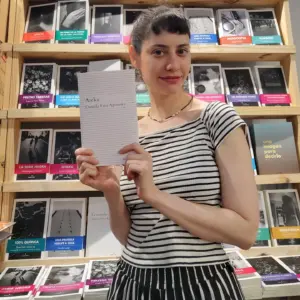

Daniela Ema Aguinsky (Buenos Aires, 1993) is a writer and filmmaker based in Argentina. She Directed the shorts Virtual Guard, Hurricane Berta, 7 Tinder Dates, and several others. She published Amante japonés, Aieka (2023) and Terapia con animales (2022) in Argentina, Mexico and Spain, book that won The National Poetry Prize Storni in 2021. She is also the spanish translator to the California based poet Ellen Bass; Todos los platos del menú (Gog & Magog, 2021). Twitter: laglu Instagram: laglus

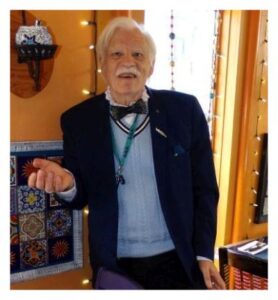

Amparo Arróspide (born in Buenos Aires) is an M.Phil. by the University of Salford. As well as poems, short stories and articles on literature and films in anthologies and international magazines, she has published five poetry collections: Presencia en el Misterio, Mosaicos bajo la hiedra, Alucinación en dos actos y algunos poemas, Pañuelos de usar y tirar and En el oído del viento. The latter is part of a trilogy together with Jacuzzi and Hormigas en diaspora, which are in the course of being published. In 2010 she acted as a co-editor of webzine Poetry Life Times, where many of her translations of Spanish poems have appeared, she has translated authors such as Margaret Atwood, Stevie Smith and James Stephens into Spanish, and others such as Guadalupe Grande, Ángel Minaya, Francisca Aguirre, Carmen Crespo, Javier Díaz Gil into English. She takes part in poetry festivals, recently Centro de Poesía José Hierro (Getafe).

Robin Ouzman Hislop is Editor of Poetry Life and Times ; at Artvilla.com

You may visit Aquillrelle.com/Author Robin Ouzman Hislop about author. See Robin performing his work Performance (University of Leeds)